The (Bumpy!) History of Acne Treatments

Would you put bird poop on your pimples? Read on for more "miracle cures"...Published:

6 minute read

Pimple, spot, zit, bump, pock, boil, blemish, carbuncle, blister...No matter what you call it, acne has been plaguing humankind for millennia. And while we’re still trying to understand its exact causes and inner workings, we’ve come a long way in terms of treatment. Here’s a look at the history of acne remedies through the ages — from the weird, to the revolutionary, to the downright disgusting.

1550 BC

Ancient Egyptian medical document the Ebers Papyrus mentions aku-t, which translates to boil, pustule, or inflamed swelling — typically treated with various animal preparations mixed with honey. Scholars speculate that King Tut had acne, since his tomb contained 10 gallons of patchouli oil — known for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties — and literally worth its weight in gold at the time. Many ancient Egyptians believed that acne was caused by telling lies, and could be cured by magic spells.

Image: Acne Remedy Recipe from the Ebers Papyrus

400-300 BC

Greek physicians (including Aristotle and Hippocrates) described a skin condition called akmḗ, meaning “facial eruption” —a word that eventually morphed into akne. It was commonly treated with plant preparations mixed with honey, which has exfoliating, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties.

1st Century AD

In his encyclopedia entitled De Medicina, Roman scholar and nobleman Cornelius Celsus wrote that although treating pimples was “almost a waste of time,” they were best remedied with “the application of resin to which not less than the same amount of split alum and a little honey has been added.” He also endorsed the popular Roman baths, particularly those containing soothing sulfur.

Image: Ancient Roman women preparing for a bath

4th Century AD

The court physician to Roman ruler Theodosius advised acne sufferers to wipe their “pimples” with a cloth while watching a falling star and claimed that the pimples would subsequently “fall from the body.” Shockingly, this treatment didn’t survive the centuries.

5th Century AD

Byzantine Greek physician and writer Aëtius of Amida includes an acne remedy in his Libri Medicinales: “Grape hyacinth burnt with bastard-sponge and then smeared on clears away acne.” In case you’re wondering, bastard-sponge is a type of Mediterranean soft coral that may have had peeling properties.

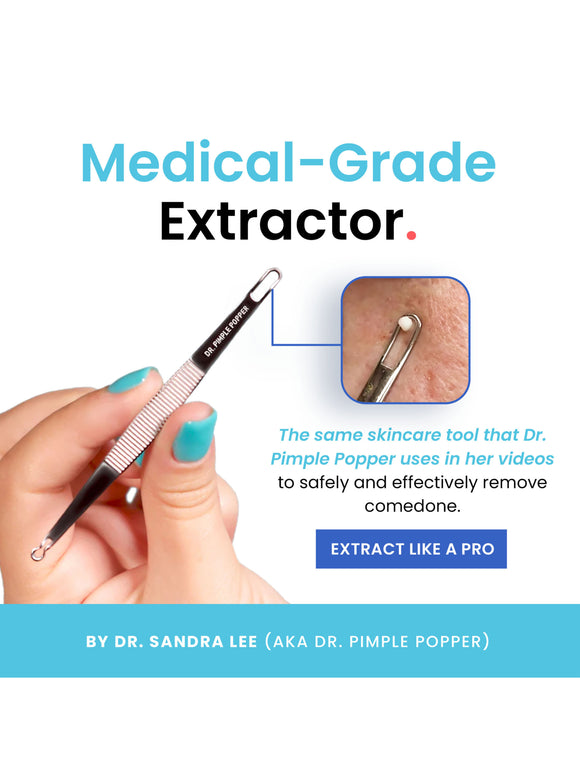

Dr. Pimple Popper's Acne Picks

700–1200 AD

Diseases (including skin conditions like acne) are largely regarded as an imbalance of the internal “humors” which could be balanced by diet, herbs, and prayers. As Europe fell into the Dark Ages, Greco-Arabic (Unani) scholars were observing cases of acne and prescribing various herbal treatments for it. Similarly, Ayurvedic practitioners treated acne (believed to be an imbalance of doshas), with herbal preparations including masks made from ingredients like turmeric (a potent anti-inflammatory), mint (rich in antioxidant vitamin A), and cinnamon (which promotes circulation).

Image: Mint and other herbs were favored by Ayurvedic practitioners

16th Century

During the 16th century Elizabethan era, women used lead-based paint to achieve pale skin — which provided ideal conditions for the formation of acne. Some people at that time associated acne with witchcraft. To treat pimples, women used highly toxic mercury-based products, which destroyed not only their blemishes, but the surrounding skin.

17th Century

The Japanese begin using uguisu no fun — translation: nightingale feces — to perfect their complexions. The bird poop is dried, crushed into a fine powder and mixed with water (and sometimes rice bran) to form a paste. Said to address hyperpigmentation and smooth skin by exfoliating, this age-old treatment has enjoyed a recent resurgence as the pricey geisha facial.

As long as we’re on the subject, urine therapy has also been used throughout the centuries to treat many skin conditions, including acne. Although urine is sterile, it becomes contaminated when we excrete it and can easily become a breeding ground for bacteria. It does contain a small amount of urea — which is an exfoliant — but not enough to make a real impact on acne.

Image: Nightingale feces were favored for facials by the Japanese

18th Century

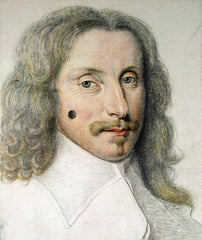

Women and men began using patches made from expensive silk and velvet (and for those who couldn’t afford better, mouse fur!) to cover up scars and blemishes left by smallpox and acne. Known as mouches ("flies" in French), the trend became so popular that some courtiers sported elaborate shapes that covered much of their faces.

Image: Portrait of a Young Man with a Beauty Spot on his Cheek

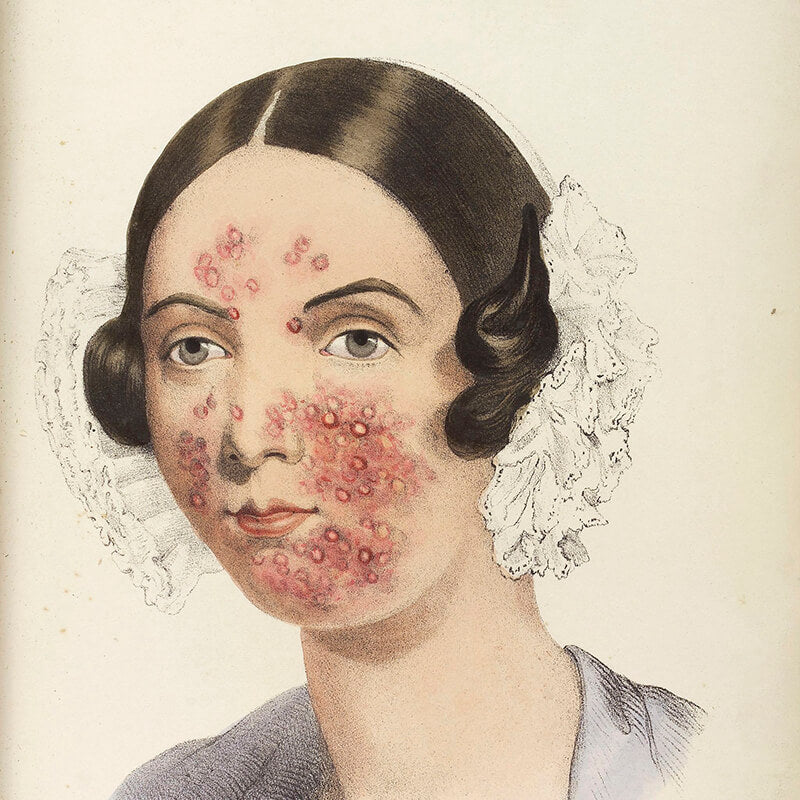

18th–early 20th Century

Advances in the fledgling field of dermatology (including the discovery of pores and sebaceous glands in 1746) laid the foundation for our modern understanding of acne. Physicians and scholars began experimenting with chemical substances like zinc oxide, sulfur, and acids (including acetic, citric and lactic) to shrink pores and combat blemishes.

Image: From TH Burgess, Eruptions of the face, head, and hands

1920

Revlon’s Jack Breitbart uses benzoyl peroxide (a drug first observed to heal burns and leg tumors) to treat acne. It’s discovered to be a more potent (and less pungent) alternative to sulfur that effectively kills acne-causing bacteria.

Try: SLMD Benzoyl Peroxide Acne Lotion

1930

Doctors theorize that acne (aka “chastity pustules”) results from a buildup of toxins caused by a lack of sexual activity in teens. Naturally, they prescribe laxatives to rid the body of these acne-causing poisons, since the alternative method of releasing them was, well, unchaste.

Up until World War II when the bombing of Hiroshima changed public opinion about the safety of radiation, X-ray therapy for acne was considered extremely effective (and often used in conjunction with laxatives). The subsequent discovery that those patients had an increased incidence of basal cell carcinoma (aka skin cancer) ultimately put an end to the practice.

Image: Laxatives have been used on-and-off in history to treat pimples

1950–1960

The FDA approves oral antibiotic tetracycline (1953) and its cousin, doxycycline (1967) — the latter of which has fewer side effects and can better penetrate to the sebaceous glands — for the treatment of moderate to severe acne.

Image: Oral antibiotics used to kill acne-causing bacteria

1971

Dr. Albert Kligman, dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, licenses his discovery of topical acne-fighting superstar tretinoin (aka retinoic acid) to Johnson & Johnson — which introduces Retin-A to the U.S. market. Kligman would later come under scrutiny for having relied on prison inmates to test dosages of the drug.

Try: SLMD Retinol Resurfacing Serum

1975

Laxatives make a comeback when a dermatologist publishes a letter (not a clinical study!) claiming that milk of magnesia — in conjunction with oral antibiotics — helped his acne patients. MoM can strip oil from skin, but it doesn’t penetrate into pores and its pH is not compatible with skin’s surface.

1982

The FDA approves oral isotretinoin (brand name Accutane) for the treatment of severe acne. Because of the potential of severe side effects (including birth defects) patients must sign a pledge prior to receiving a prescription for the highly-effective drug.

2000–Today

Light and laser therapy gains popularity based on an ability to reduce C. acnes bacteria, inflammation, and oil production. These modalities are most effective for treating moderate to severe inflammatory acne when combined with more traditional treatments, like oral antibiotics or isotretinoin. Lasers and light are also useful for addressing acne scarring.

Image: Laser light therapy for acne

Image Credits

- Image: Acne Remedy Recipe from the Ebers Papyrus, Wellcome collection, available on Wikimedia Commons

- Yves Jalabert from Région parisienne, France, CC BY-SA 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

- "Mint" by James Jardine is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Portrait of a Young Man with a Beauty Spot on his Cheek by Daniel Dumoustier, public domain

- From TH Burgess, Eruptions of the face, head, and hands: with the latest improvements in the treatment of diseases of the skin, Wikimedia Commons

- "Vintage Tins of Ramon's Mild Laxative Pills, Trade Mark - 'The Little Doctor', NOS" by France1978 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Dr. Lee's Last Word

When it comes to treating acne and other skin conditions, there are a host of proven ingredients — some of which have been used for centuries, like sulfur and lactic acid — that are still in use today. Patients today are better off than in the past, because we’ve also got an arsenal of powerful treatments like retinol, benzoyl peroxide, and antibiotics. As a dermatologist, I’m always keeping up with what’s happening in the field, so when new advances are made, I’ll incorporate them into my practice.